ADULT FUN

ADULT FUN

UK | 1972 | Colour | 102 mins

Credits:

Director and Writer: James Scott

Cinematographer: Adam Barker-Mill

Producer: Tim Van Rellim

Composer: Simon Standage

Music Performed by: Simon Standage

Trevor Pinnock

Film Editors: Adam Barker-mill

Jon Sanders

James Scott

Sound Recordist: Tony Jackson

Assistant director: Robert Henderson

Boom operator: Steven Ransley

Casting: Lindsay Ingram

Continuity: Jaki Nellist

Driver: Dave Strong

Dubbing mixer: Peter Gilpin

Music Coordinator: George Howe

Mike Hutson

Camera assistants: Nigel Branwell

John Pasmore

Deborah Youens

Photography: Andrew Lanyon

Properties: Wilfrid Scott

Selected Cast:

(For more information, see page for FULL CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

Role … Actor

Chris Thompson … Peter Marinker

Jenny … Deborah Norton

Mary Thompson … Judy Liebert

Artist … Bruce Lacey

Artist’s Wife … Jill Lacey

Other Woman Friend … Beryl Bainbridge

Stockbroker Boss … Ron Pember

Mrs Taylor, Mary’s Mother … Florrie Ingram

Mr Taylor, Mary’s Father … Peter Chapple

Garage Manager … Michael Elphick

Man In Cinema Reading … Marc Karlin

Girl Behind Counter In Café … Sally Bell

Mr Yates, The Contact … Dennis Tynsley

Mr Charles … Roger Booth

Karl, Mr Bryant’s Assistant … Carl Howard

Mr Bryant, Private Detective … Roger Hammond

Plainclothes Police … Tom Kempinski, Noel Collins

Sex Worker … Ann Foster

Synopsis

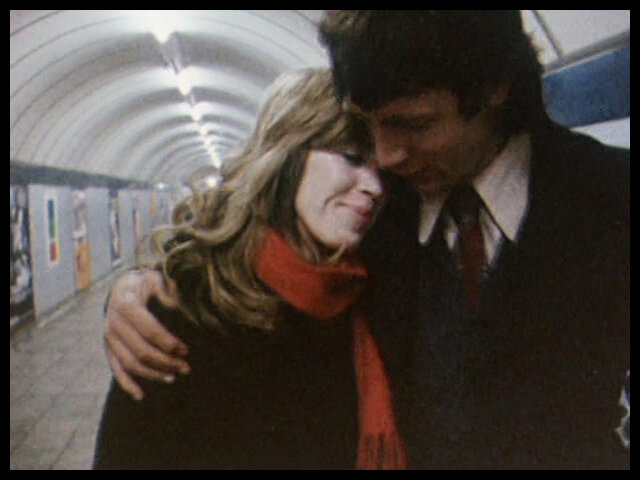

This semi-documentary thriller is set in the world of industrial espionage. The hero, Chris Thompson, already employed by the “organization” to spy on another firm, finds himself being followed by a private detective agency.

German film critic, Reiner Weiss compared Scott’s style here to Hitchcock’s, whereas, Duke Dusinberre of Time Out compared it to Godard’s in it’s combination and parody of genres. Many of the cast are non-professionals and much of the dialogue is improvised.

Director’s Notes

This was my return to narrative after my first short, The Rocking Horse. I had become immersed in another strand of cinema, documentaries about artists: David Hockney, RB Kitaj, Richard Hamilton, and Claes Oldenburg.

So ten years on, while working on a new script based on the tragic story of Gaudier-Brzescha, an artist who was killed in WW1, I became involved in a political documentary film, Nightcleaners, about people who worked for minimum wage at night, exploited and unseen.

Significantly, it was at this time that I also began work on a new script for an independent feature, then titled Transformation which would become Adult Fun. Here I wanted to interweave the many strands of cinema that I had been obsessed with since The Rocking Horse to include the vision of Graham Greene. As an ex-pat Englishman, in many of his novels, he was dealing with that deep sense of alienation, the malaise, that like a virus was infecting the very core of people’s lives in the UK and abroad.

I wanted to portray that alienation in a physical way through the use of the medium itself. What I did not reckon with, was the anxiety that the film would create in viewers. Unlike my film about Hamilton, where the mix of genres was nicely explained while the audience could sit back and enjoy, here the viewer is propelled to the forefront of the action, unsure of how to mediate the conflicting messages that are being propelled towards them. There is no easy emotional map. It was a film that unintentionally polarized audiences, and yet, in the words of John Lewis, was ‘good trouble’.

James Scott

August, 2020

Reviews

Time Out London

by Duke Dusinberre

The influenza of Italian and French assaults on narrative film-making (during the '50s and '60s) eventually spread to Britain (in the '70s); and one of the more interesting cases is this rather opaque film. It looks very Godard-like in its combination and parody of genres (potboiler fiction, documentary, pseudo-documentary) and in its action-packed plot, which pivots on underworld crime as a young stockbroker suffering from feelings of alienation becomes nightmarishly involved, Graham Greene style, in industrial espionage. Scott got one step ahead of Godard, however, in the complex mixing of the soundtrack so that words do not merely accompany the image, but must be problematically deciphered against it.

MFB, vol 40 no 47, Dec 1973

by Richard Combs

(EXCERPT)

… An opaque, metaphysical thriller which strangely combines elements of early Godard with the downtrodden moods and seedy milieu of Graham Greene. The two strands work heavily in opposition, with the latter-predominating, mainly because of the vivid local detail with which James Scott manages to characterize all the underworld corners of the plot, and the film’s attempt at more abstract speculation inevitably languish in these stifling labyrinths. Like the hero of ‘Le Petit Soldat’, Chris Thompson lives at a distant remove from himself and the violence (either real or fantastic) which he dispenses as a way of affirming his identity, and which inevitably rebounds on him, fulfilling his paranoid expectations and grotesquely snuffing out his life. In James Scott’s free intermingling of dramatic fiction with semi-documentary material, Chris’ encounters in the mysterious by-ways of the ‘organization’ – the graying, tight-lipped man, for instance, who hands him the gun and responds to questioning by confessing that he is ‘bitterly disappointed’ and envious of the wife who is ‘more of a success then I am’ – turn into interviews in which the subject, like the hero, are challenged by doubts similar to the questions, that echo through ‘Le Petit Soldat: Where have you come from? Where are you? Where are you going?’ The film becomes a network of enclaves (the offices of the detective and the espionage people; the presumably authentic reminiscences of the lavatory attendant, the down-and-outs and the prostitute in the cine-verite interviews), usually heavy with an air of threatened violence, and more powerful as a paranoid vision of society than the rather abstract, Kafka-esque models more typical of English movies (Peter Sykes ‘The Committee”, for example); in fact closer to the shabby detail of Greene’s ‘Ministry of Fear’. A multitude of references are built up round the hero; in his impotent anxieties, he is afflicted with Sartre’s nausea, and Poe’s William Wilson is quoted by the private detective who describes Chris as ‘a schizophrenic, a very dangerous man’. But although ‘Adult Fun’ faithfully fragments the world as it is seen through Chris’ frightened and paralyzed imagination, the character himself is a very shaky center, too ill-defined either for his own agonies of identity to hold attention, or to focus the diverse mock-thriller elements and the more general speculations. For Scott clearly sees Chris Thompson as only one ‘hero’ among many, or simply as a pointer to a general condition, reducing him to a neutral question-machine during the long-held takes on the interviewees and, during one scene in a café, slipping away from him to study, in successive close-ups, the girl sitting blankly behind the counter. But with the guide reduced to a cipher, much of the terrain of ‘Adult Fun’ remains an incomprehensible mystery.

FINANCIAL TIMES, August 11th, 1978

“JS retrospective at the National Film theatre” by Geoff Brown

Faced with the mindless spectacle of Midnight Express, it’s especially pleasant to welcome the National Film Theatre’s brief season in its new “British Independent Film Maker’s” slot, devoted to the films of James Scott – for Scott’s work has always been concerned with the varied and ambiguous ways of conveying specific information through the screen image. He first made his mark in the late 60’s with a group of art documentaries which cut straight against the accepted style as promoted by the Arts Council (though their output is now much livelier). Then, films on artists seems to consist of one masterpiece dissolving into another, accompanied by dignified commentary, classical sounds and an unseen aura of immense sanctity. Scott’s films on David Hockney (Love’s Presentation), Richard Hamilton and Claes Oldenburg (The Great Ice Cream Robbery), removed the aura, showed us in detail the technical processes involved in producing etchings, or the influences and components which make up a “pop” artist.

The art films have sadly been and gone; it is also too late to see Scott’s first feature Adult Fun (1972), which takes place in a stylistic no man’s land, shifting uneasily but fascinatingly between the dingy urban thriller, outright fantasy and documentary interviews. The adult fun involves industrial espionage with a dislocated hero hired (in a suburban room with fulsome wallpaper) to dispose of a business man who pads around in white shoes. The film was generally given a cold shoulder when it first emerged, but it deserves extended public exposure, particularly as urban and industrial malaise has only worsened in the intervening six years; its perilous balancing act between various styles makes for worrying, engrossing viewing. And the film can only gain by being seen in the context of Nightcleaners showing on August 21, made between 1970 and 1975 by the Berwick Street Film Collective, Scott included. From the “contract cleaners” of Adult Fun to night cleaners working in office blocks isn’t such a big jump: both worlds involve managerial double-dealings hidden away behind anonymous familiar buildings. And Scott’s increased political concern has only heightened his insistence on clarifying the methods used to present his findings on the screen. Other items in the season are Coilin and Platonida (August 14), a feature shot with non-professionals in Ireland, and the first showing of the Nightcleaners sequel, ’36 to ’77 (August 22). Stimulating British independent cinema does not reach the cinema all that often; when it does, it deserves every support.

.